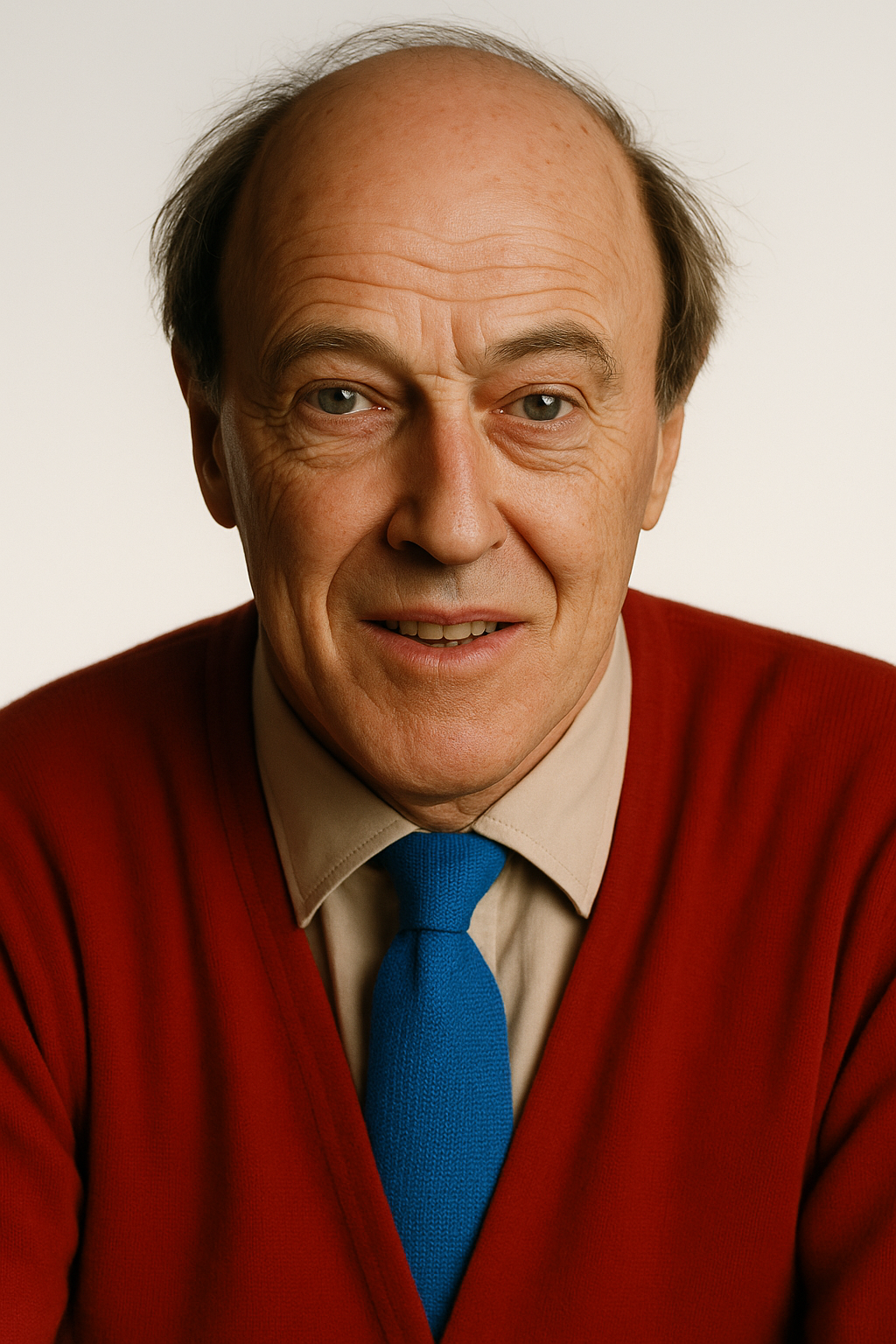

Roald Dahl was one of the most influential and imaginative storytellers of the 20th century, known for blending dark humor, vivid characters, and moral lessons into captivating tales for children and adults alike. Born in Wales in 1916 to Norwegian parents, Dahl served in the Royal Air Force during World War II before turning to writing. His distinctive voice, whimsical plots, and deep empathy for children made his works classics, enduring across generations. He crafted a world where children often face cruel adults but ultimately triumph through cleverness, courage, or magic.

Among his many beloved works, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and Matilda stand out as global favorites. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory follows poor but kind-hearted Charlie Bucket as he wins a golden ticket to visit Willy Wonka’s magical chocolate factory. There, he encounters other children who fall victim to their flaws—gluttony, greed, vanity—while Charlie’s humility earns him an unexpected reward. Matilda tells the story of an extraordinarily gifted girl neglected by her ignorant parents and bullied by the monstrous headmistress Miss Trunchbull. With the help of her telekinetic powers and kind teacher Miss Honey, Matilda asserts justice and finds a loving home.

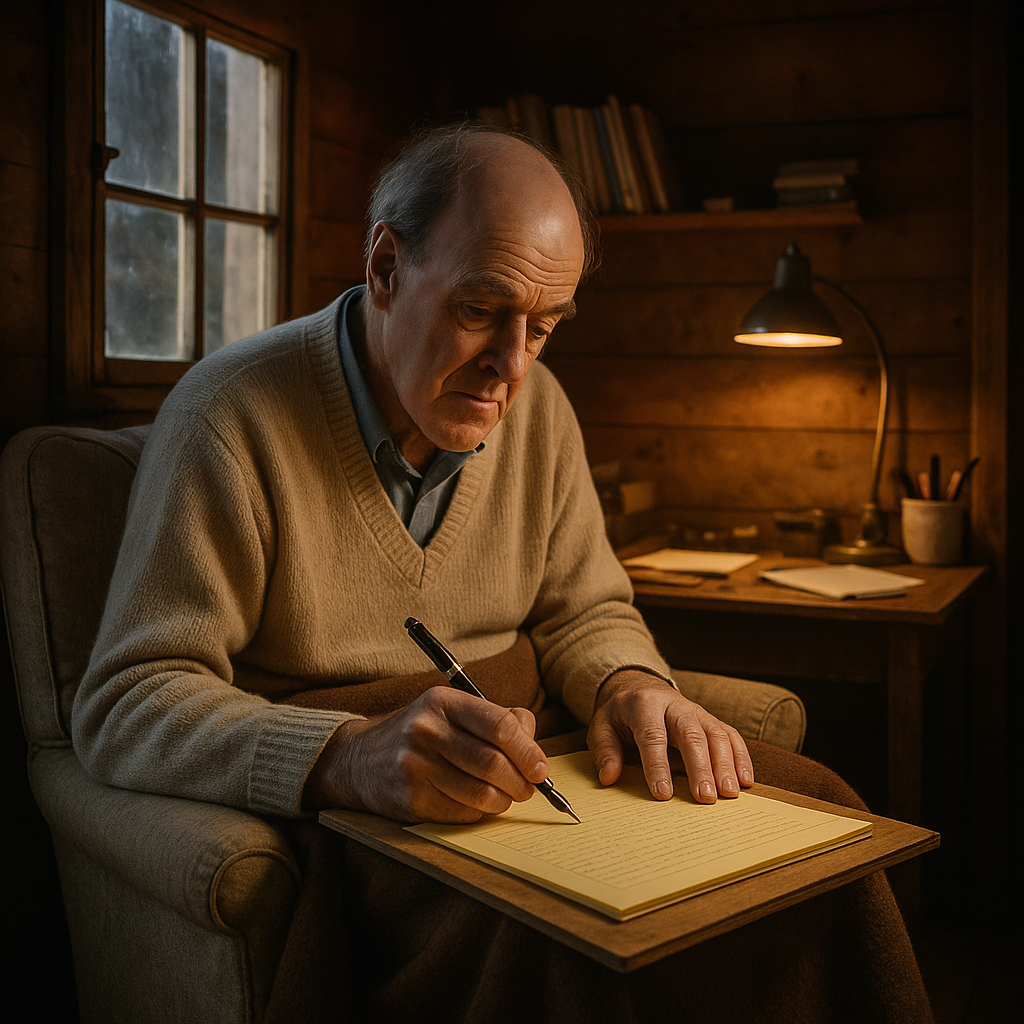

Dahl was famously fond of writing with fountain pens, and his disciplined routine reflected his deep respect for the writing process. Though he often began brainstorming and drafting with sharpened Dixon Ticonderoga pencils, he preferred to write the final versions of his manuscripts using a fountain pen, typically on yellow legal pads. He was particular about his environment as well—writing in a small, warm hut at the bottom of his garden in Great Missenden, Buckinghamshire, wrapped in a sleeping bag on his armchair, using a wooden board as a desk.

It is widely believed that Dahl used high-quality fountain pens such as the Montblanc 149 or Parker models, which were known for their smoothness and reliability. He appreciated the tactile quality of handwriting and the precision of ink on paper. His tools and routine were not just habits—they were part of a ritual that grounded his creativity and allowed his unique imagination to flourish. His preference for analog tools echoed the simplicity and clarity of his storytelling, despite its often surreal content.

Dahl frequently expressed his political views, including criticism of zionists’ treatment of Palestinians during the Lebanon War. His remarks drew both support and condemnation.