The fountain pen, i.e. that elegant reservoir of ink and intellect, did not arrive fully formed from the minds of nineteenth-century inventors. It was the culmination of centuries of refinement, the answer to a perennial challenge: how might one write fluidly without constant interruption to replenish ink? Before Waterman’s clever feed mechanism or the gentleman’s pocket clip, there was the quill—humble in origin, yet unrivalled in its contribution to human thought. For nearly a thousand years, this sharpened feather served as the principal writing instrument of the world, etching scripture, law, poetry, and revolution into parchment and paper alike.

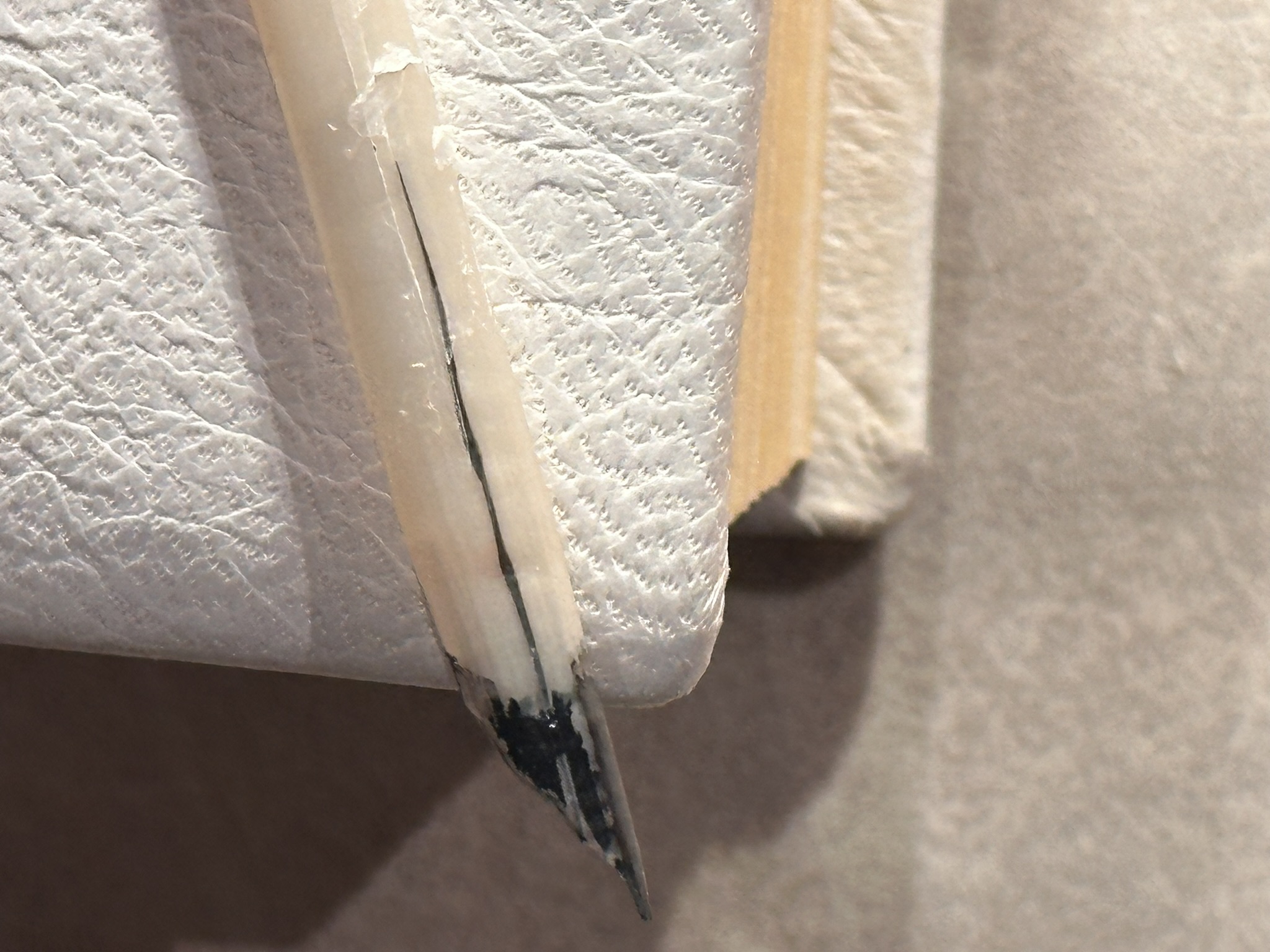

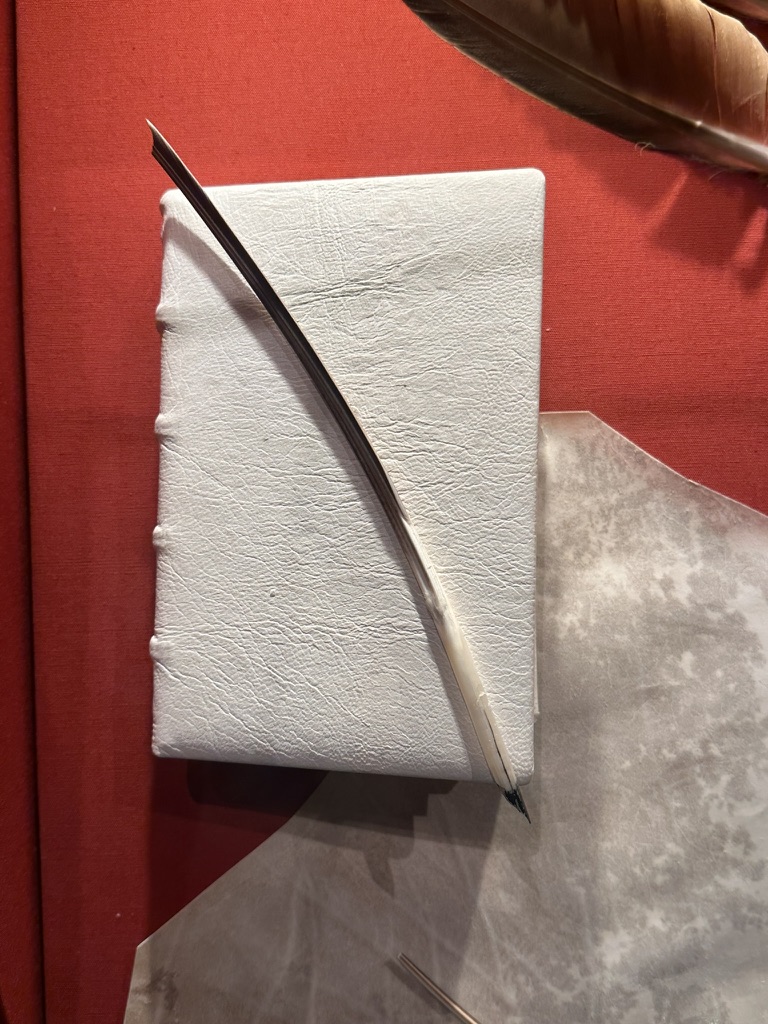

A well-made quill is a marvel of natural engineering. Drawn from the flight feathers of geese, swans, or turkeys, its hollow shaft functions as both reservoir and conduit. With care and craft, the calamus is cured—hardened through heat and stripped of its soft pith—then carved with a penknife into a nib that flexes ever so slightly under the hand. The slit cut into its point permits ink to flow through capillary action, and the result is a line that can dance from whisper-thin to richly bold with the mere flick of a wrist. In the right hands, it becomes not merely a writing tool, but a brush for thought.

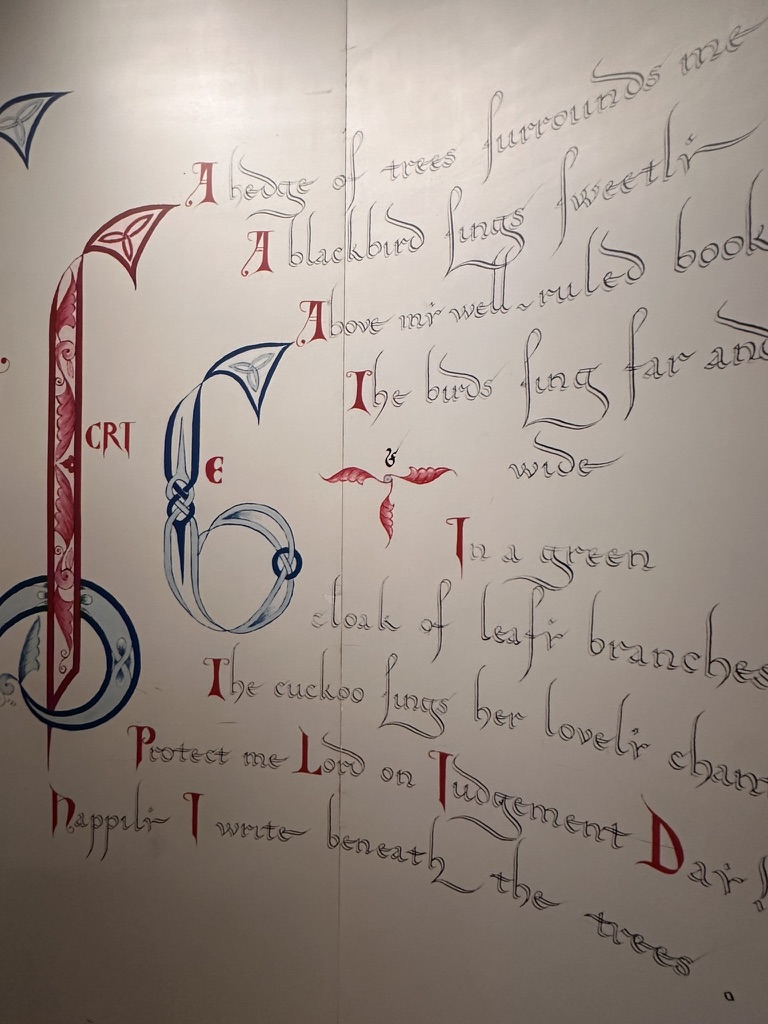

The quill’s heyday stretched from the early Middle Ages into the nineteenth century. Monastic scribes toiled by lamplight, copying sacred texts with painstaking fidelity. The Book of Kells, the Lindisfarne Gospels, and countless illuminated manuscripts were born beneath the rhythm of dipping and scratching. In the courts and chancelleries of Europe, laws were drafted and sealed under the sharp tip of the quill. And in the bustling city of London, William Shakespeare inked the immortal lines of Hamlet and King Lear, dipping his feather into a dark inkwell as actors rehearsed their lines by candlelight.

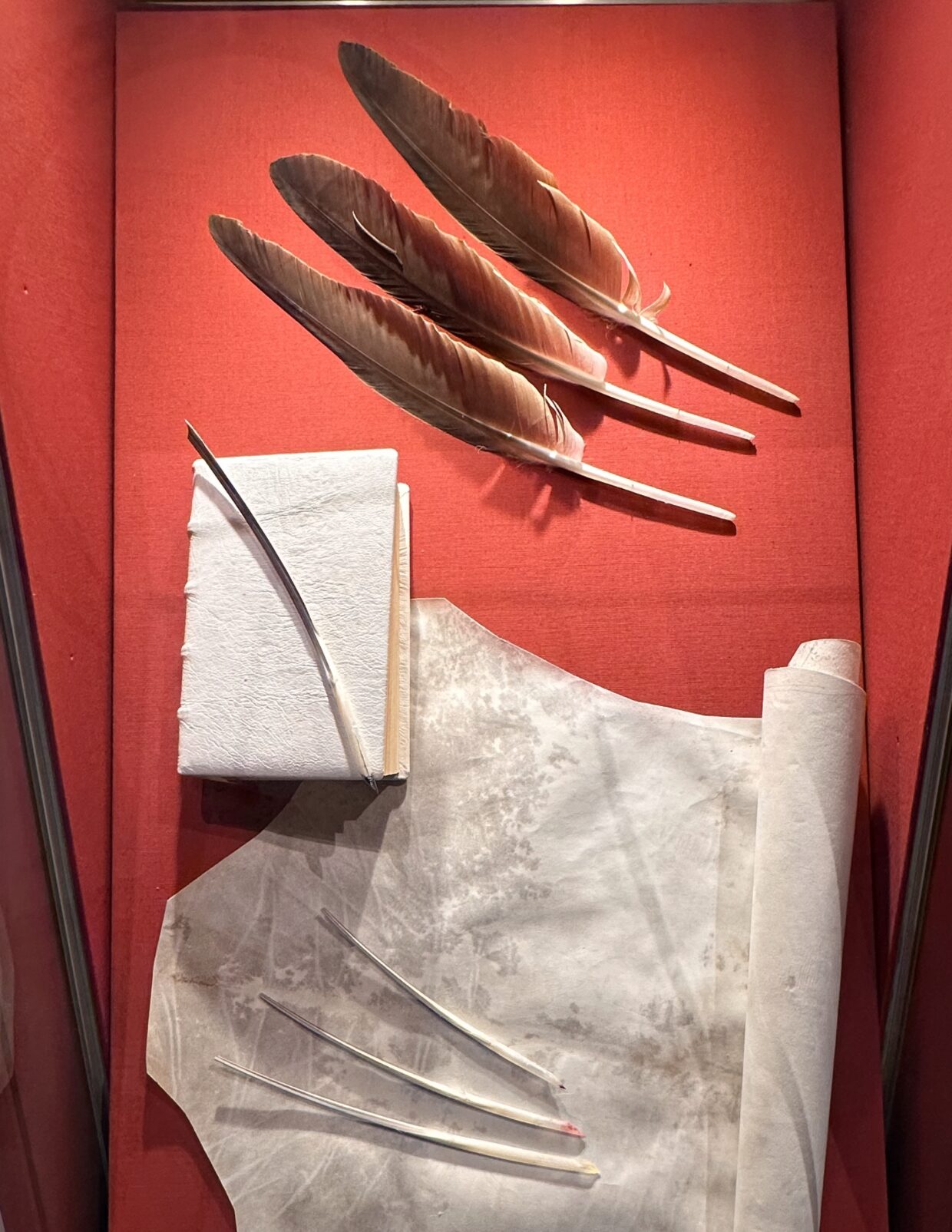

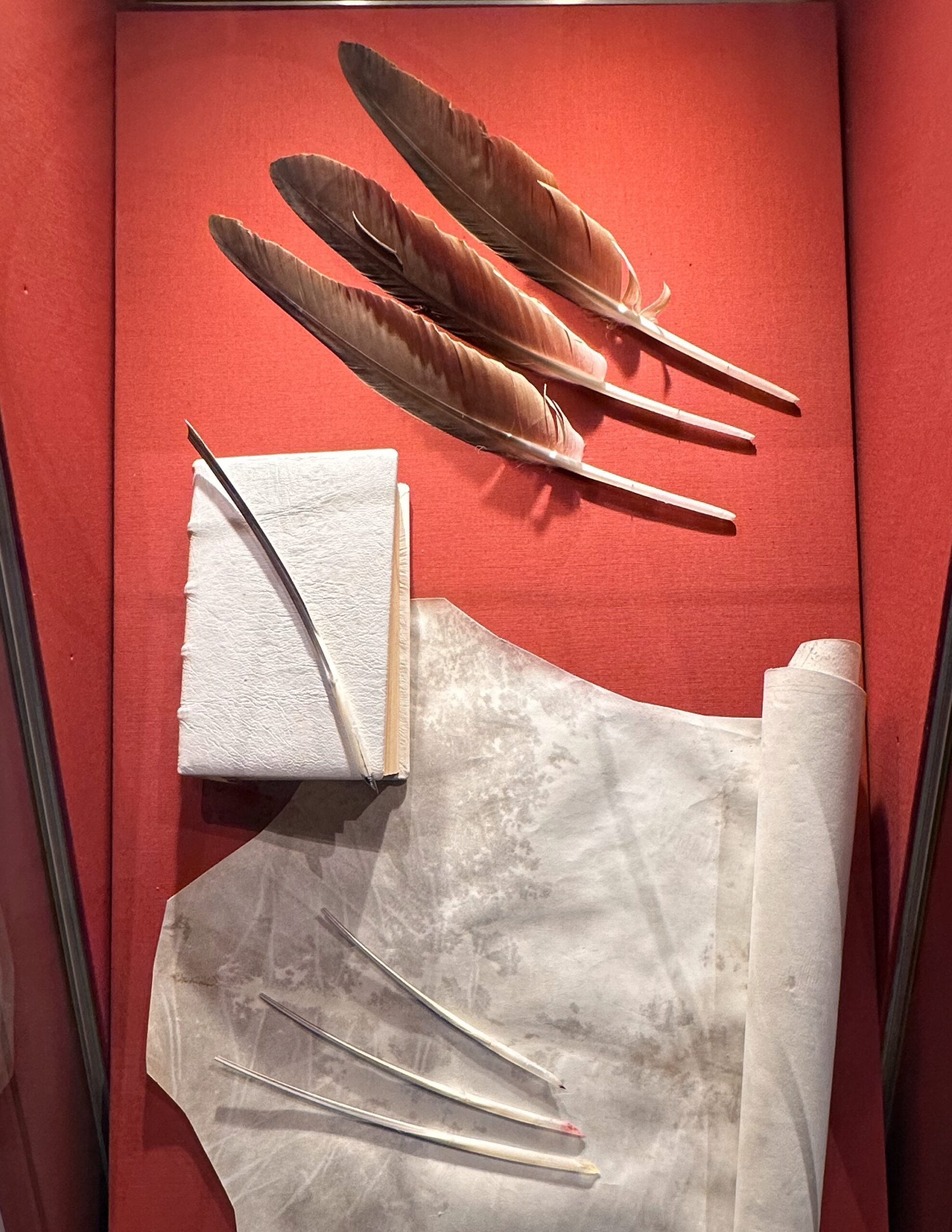

The quill was not merely a writer’s tool—it was a craftsman’s companion. A single feather, properly cut and maintained, might serve for a few days’ work, though professional scribes often kept several at hand, each suited to a different purpose: one for fine marginal notes, another for bold headings, a third trimmed anew after the previous had worn dull. A penknife was always near—not for defence, but for reshaping a tired nib. Ink, typically iron gall, was caustic and permanent, requiring precision and care, lest a blot undo hours of labour.

Even as Enlightenment dawned and printing presses multiplied, the quill remained in daily use. Thomas Jefferson, that restless correspondent, kept a flock of geese at Monticello partly to secure his own supply. The Declaration of Independence, so often read in solemn tones, was transcribed by hand with a quill. And across Europe, philosophers, poets, and reformers carried feathers in their writing boxes, trusting them with the weight of revolutions both political and poetic.

But progress, relentless as ever, rendered the quill increasingly impractical. The 1820s saw the rise of machine-stamped steel nibs in Birmingham—durable, uniform, and cheap. These metallic successors required no feather, no curing, and no cutting. By the late nineteenth century, the fountain pen had arrived, its internal ink feed solving the quill’s great inconvenience: the need to dip. By the mid-twentieth century, the mass-produced ballpoint had dethroned them all, trading grace for utility. Then, surely, entered the computer era.

Yet the quill did not vanish entirely. In the hands of calligraphers, it remains a living tool. The United States Supreme Court lays a white goose quill at each counsel’s desk, an emblem of legal gravitas. Artists and historians have revived the craft, cutting and tempering feathers not merely as anachronism, but as homage to a tradition in which the act of writing was itself a form of ceremony.